-

结直肠癌(CRC)是最常见的消化道恶性肿瘤,在中国的发病率仅次于肺癌,且呈逐年升高的趋势[1]。结直肠癌的发病机制具有多因素、多阶段、多基因突变等特点[2-3]。结直肠癌早期发现的概率低,多数患者出现明显症状后才被确诊,此时手术通常已无法完全控制肿瘤进展,需化疗控制病情[4]。结直肠癌患者最常用的化疗药物为奥沙利铂和五氟尿嘧啶(5-FU),分别是DNA合成抑制剂和胸苷酸合成酶抑制剂,影响细胞DNA复制和转录,最终导致细胞死亡[5-7]。近年来,复发或难治性结直肠癌患者数量逐渐升高,对多数化疗药无应答,其5年生存率低于10%[8-9]。结直肠癌患者耐药情况越来越严重,解决耐药问题的首要条件为阐明结直肠癌患者化疗耐药的机制。

随着人们对肠道微生物研究的深入,已明确表明其与多种肠道疾病相关,其中具核梭杆菌(Fn)与结直肠癌发生、发展的关系研究最透彻[10-13]。在口腔、胃肠道、呼吸道等环境内均明确发现Fn,是一种专性厌氧性、G−菌,可黏附、侵入细胞,获得适合生存的环境[14-16]。Fn可以产生毒力因子、提升白介素17(IL-17)和肿瘤坏死因子(TNF)等促炎因子水平、抑制自然杀伤细胞的细胞毒活性、招募肿瘤浸润性骨髓细胞等,促进肿瘤发生、发展和耐药机制的产生[11-13, 17-19]。例如,Fn促进了CRC的进展,并使奥沙利铂和5-FU化疗耐药[20]。因此,解决Fn高富集后促进CRC进展并产生化疗耐药的问题,有望提升结直肠癌患者化疗的有效率。

本研究首先在类器官层面验证Fn促结直肠癌增殖作用,其次比较考察前期筛选获得的抗Fn化合物在Fn与结肠癌HCT116细胞共孵育条件下对其体外抗癌活性的影响,最后优选高活性化合物开展其对Fn灌胃干预下裸鼠结肠癌HCT116移植瘤抗癌药效评价,为新型抗结直肠癌药物研发提供先导化合物。

-

基于市售化合物库(上海陶术生物科技有限公司)中5073个化合物针对Fn的表型筛选结果,选择9个不同结构类型、不同作用机制、不同活性的化合物作为本研究的实验材料;鼠源PD-1(程序性死亡受体1)抗体(武汉艾美捷科技有限公司);布氏肉汤、脑心浸出液(BHI)肉汤(美国BD公司);结直肠癌类器官基础培养基、培养基补充液B、培养基补充液C、类器官培养型基质胶、肿瘤组织消化液和红细胞裂解液(伯桢生物科技公司);直肠癌组织(海军军医大学第一附属医院肛肠科);DMEM培养基、CCK-8检测试剂盒、胎牛血清(上海翌圣生物科技股份有限公司);人结直肠癌细胞HCT116(上海中国科学院细胞中心);具核梭杆菌(ATCC 23726

, 美国模式菌种收集中心);裸鼠(上海吉辉实验动物饲养有限公司);xCELLigence RTCA DP实时无标记细胞分析仪(安捷伦科技有限公司)。 -

①实验前准备:首先,配置完全培养基(结直肠癌类器官基础培养基∶培养基补充B∶培养基补充C=976∶20∶4);其次,将−20℃保存的类器官基质胶放置于4℃融化(室温下不超过30 s);最后,将肿瘤组织消化液置于37℃的水浴锅内预热。②组织收集与处理:直肠癌组织用类器官基础培养基清洗2遍,置于盛有PBS的无菌培养皿中,无菌剪刀剪碎组织至直径小于1 mm,然后用适量的肿瘤组织消化液重悬,并转移至离心管内,于37℃、100 r/min的恒温振荡培养箱中消化30 min,在消化完成的组织悬液中加入胎牛血清(FBS)至终浓度达1%~5%,减缓消化作用,同时轻轻吹打5~10次。③筛选细胞:用100 μm细胞过滤器过滤组织悬液,将穿过的滤液转移至离心管中,450 r/min离心3 min,吸去上清液。④细胞收集:用类器官基础培养基清洗细胞2次,加入红细胞裂解液裂解1 min,300 r/min离心3 min,吸去上清液。⑤3D培养板细胞接种:按每孔2×103个细胞用20 μl基质胶于冰浴条件下混匀,然后用移液器将基质胶和细胞的混合液移至细胞培养24孔板底部中央位置,于37℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱中孵育15 min。⑥加液培养:待培养24孔板基质胶凝固至不再流动后,沿孔壁缓缓加入完全培养基,于37℃、5% CO2培养箱中培养。⑦加Fn菌液:培养72 h后,观察类器官成型且稳定,采用完全培养基重悬Fn使其浓度分别为1×108 CFU/ml和1×104 CFU/ml,加入24孔板中,同时在不同孔中加入同体积PBS。⑧观察:每天在同一视野、同一放大倍数下分别对PBS、浓度为1×104 CFU/ml和1 × 108 CFU/ml的Fn作用下的直肠癌类器官进行拍照记录,观察类器官生长变化,共4 d。

-

①细胞培养:用8 ml含10%胎牛血清和1%双抗的DMEM培养基培养HCT116细胞。待细胞生长至 90% 左右时,弃上清液,加入2 ml PBS清洗,2 ml胰酶消化1.0 min,加入3 ml含10%胎牛血清和1%双抗的DMEM培养基吹打均匀,1 000 r/min离心5 min后,弃去上清液,加入4 ml含10%胎牛血清和1%双抗的DMEM培养基再次吹打均匀,取10 μl细胞悬液稀释10倍至100 μl,置于细胞计数板上计数。②细胞铺板:将HCT116细胞按照浓度为每孔7 × 103个/ml加100 μl于96孔板中,37℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱中孵育12 h。③受试药物与细胞或与细胞和Fn共孵育:吸出培养基,每孔加入100 μl不同浓度的受试化合物,将生长良好的Fn培养液用4 000 r/min离心10 min,弃上清液,加入无胎牛血清、无双抗的DMEM培养基混匀,比浊仪将菌的浓度调至0.5麦氏浊度[(1~2)×108 CFU/ml]制得Fn菌液,然后再加入100 μl感染系数(MOI)为1 000∶1的上述Fn菌液或新鲜无胎牛血清和双抗的DMEM培养基,于37℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱中培养72 h。④测定IC50:吸出培养基,加入100 μl浓度为10%的CCK-8溶液,35℃孵育0.5 h,在450 nm波长的条件下读取A值;用GraphPad Prism 7软件拟合出受试药物对HCT116细胞或与Fn共孵育HCT116细胞的IC50值。

-

①HCT116细胞培养和Fn菌液准备同“2.2”项。②按实时无标记细胞分析仪的规范操作程序完成名称、目的、分组、时长等输入。③以50 μl含5%胎牛血清、无双抗DMEM培养基进行基线矫正。④每孔加入7×103个/ml 的HCT116细胞,在室温下放置 30 min后,放置于测试台中。⑤ 18 h后暂停设备,吸出培养基,加入含5%胎牛血清、无双抗DMEM培养基的Fn菌液100 μl,使得MOI=1 000∶1,加入浓度在最小抑菌浓度(MIC)上下的受试化合物100 μl,放入测试台中继续培养72 h,实时观察记录HCT116细胞数量变化。

-

①裸鼠在动物房无操作下饲养5 d,然后在裸鼠饮用水中加入链霉素和克林霉素使其浓度分别为5 g/L和0.1 g/L,继续饲养7 d以清理裸鼠肠道微生物,减少其他微生物对实验结果的影响。②以皮下注射方式,接种浓度为1.0×107个/ml的人源HCT116细胞。③待皮下肿瘤大小长至50 mm3时,将浓度为1×108 CFU/ml(BHI溶解)的Fn菌液灌胃,每2 d给予1次,500 μl/只,共4次。④将荷瘤裸鼠随机分为4组,对照组和PD-1组每组5只,甲氨蝶呤组和联合用药组每组3只。对照组:每3 d给予Fn灌胃1次;PD-1组:除每3 d Fn灌胃1次外,另外给予鼠源PD-1抗体腹腔注射100 μl,首周3次,次周2次,每次给药剂量为5 mg/kg;受试药物组:除每3 d给予Fn灌胃1次外,再给予甲氨蝶呤灌胃500 μl,剂量为0.5 mg/kg,每天给药1次;联合用药组:采用同样的给药频率和剂量,同时给予甲氨蝶呤和PD-1抗体。⑤裸鼠体质量和肿瘤体积监测:每天监测荷瘤裸鼠体质量和皮下肿瘤体积变化,观测15 d后断颈处死裸鼠。肿瘤体积计算公式为V=1/2×a×b2,式中a为肿瘤长径,b为肿瘤短径。抑瘤率(%)=(对照组平均体积−实验组平均体积)/对照组平均体积×100%。

-

实验处理及统计图表的绘制利用GraphPad Prism软件完成。符合正态分布计量资料用(

$ \bar{x}\pm \mathrm{s} $ )描述,进行方差分析或t检验,计数资料采用$ {\chi ^2} $ 检验。P<0.05为有统计学差异。 -

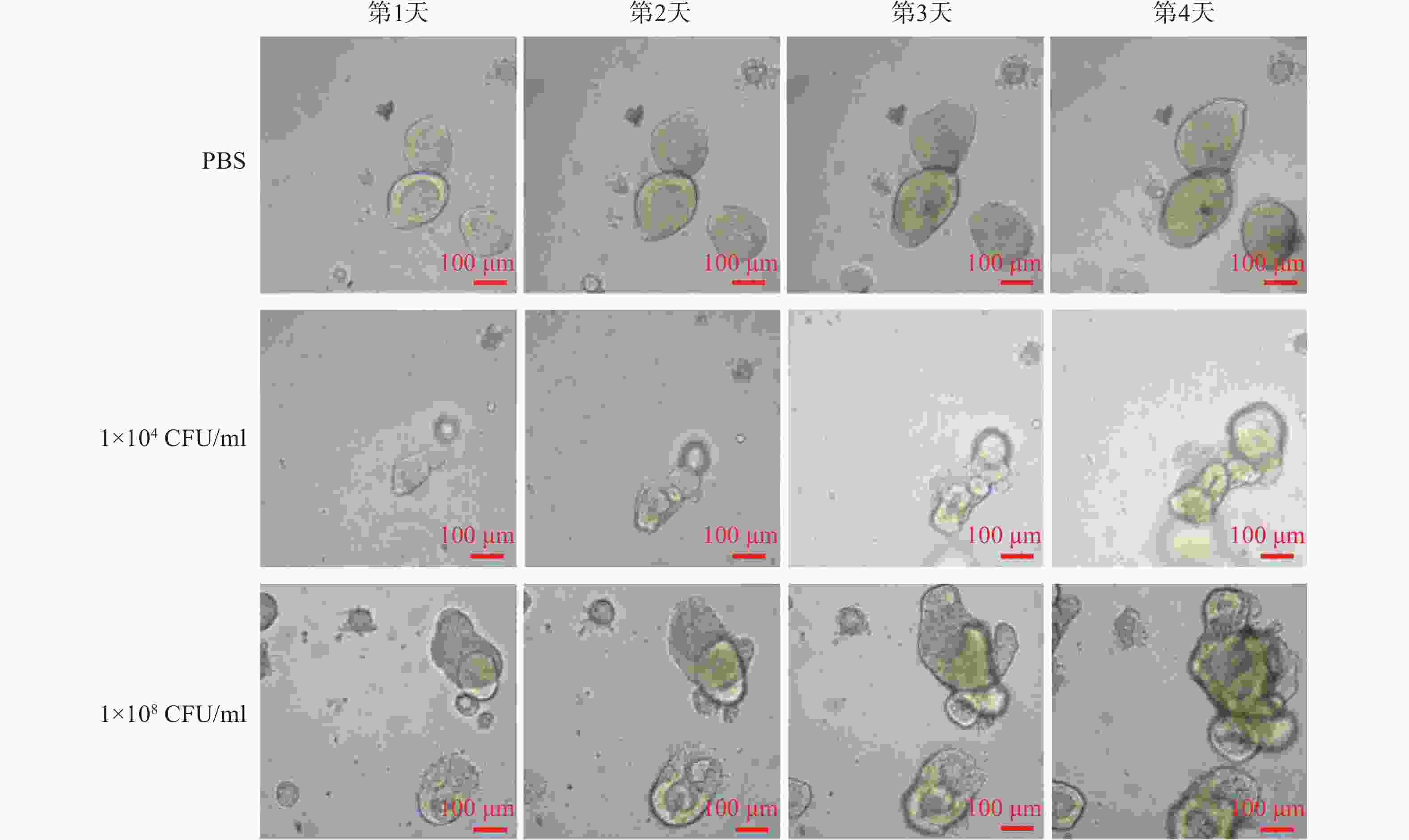

连续4 d对PBS和不同浓度Fn干预下的固定位置直肠癌类器官生长情况的拍照观察结果显示,PBS阴性对照组的直肠癌类器官随时间呈缓慢生长;但是,1×104 CFU/ml浓度的Fn干预下的直肠癌类器官随时间呈急速生长,且呈浓度依赖(图1)。

-

用CCK-8法分别比较测定了前期筛选获得的9个MIC达2.0~32 μg/ml的抗Fn活性化合物对人结直肠癌HCT116细胞及在最优MOI条件下与Fn共孵育的人结直肠癌HCT116细胞的体外IC50,结果显示,9个受试化合物均能显著提升Fn与结肠癌细胞共孵育条件下的体外抗肿瘤活性,其中甲氨蝶呤提升幅度最大,达143倍(表1)。

表 1 Fn对抗Fn化合物(MIC)的体外抗癌活性(IC50)的影响

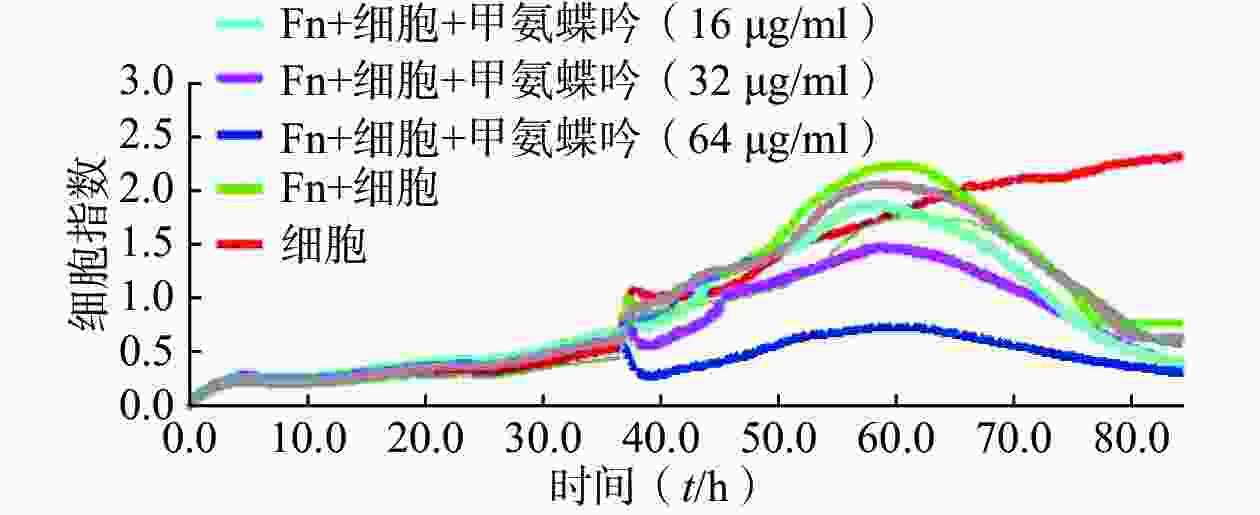

名称 MIC

(μg/ml)HCT116

(IC50,μmol/L)HCT116 + Fn

(IC50,μmol/L)新鱼腥草素钠 32 0.48 0.12 对甲氧基苯甲醛 32 4.22 1.77 PA-824 32 9.62 5.62 甲氨蝶呤 32 4.30 0.03 吲哚-3-甲酸 16 8.86 2.72 己烯雌酚 32 23.10 9.35 2'-脱氧胞嘧啶核苷 8 0.78 0.07 5-硝基-8-羟基喹啉 2 22.85 3.93 特地唑胺 2 4.29 1.42 通过实时无标记肿瘤细胞分析技术检测了优选抗Fn活性化合物甲氨蝶呤在Fn与HCT116细胞共孵育条件下对肿瘤细胞生长的影响,实时检测结果显示,甲氨蝶呤也能显著抑制Fn的促肿瘤细胞生长作用,且呈浓度依赖性(图2)。

综上所述,优选甲氨蝶呤开展后续Fn灌胃干预下裸鼠人结肠癌HCT116移植瘤的体内抗癌药效评价。

-

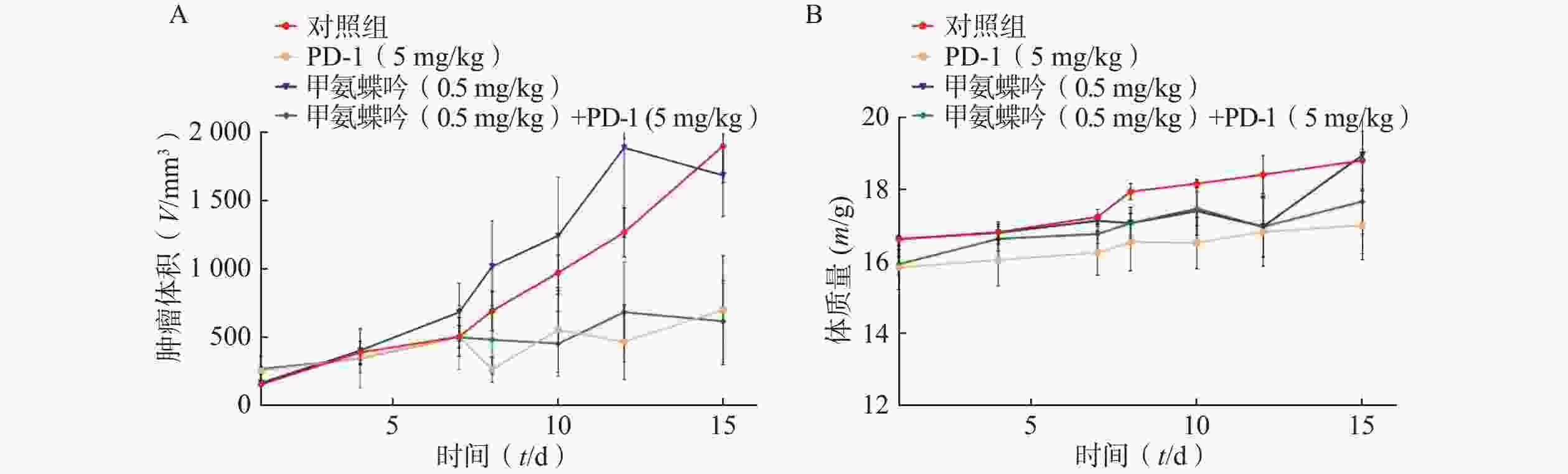

在Fn灌胃干预下,抗Fn优选化合物甲氨蝶呤(0.5 mg/kg) 以及PD-1抗体 (5.0 mg/kg) 单独用药的抑瘤率分别为 11.39%、 53.95%; 当甲氨蝶呤 (0.5 mg/kg)与PD-1抗体(5.0 mg/kg)联用后,其抑瘤率可显著提升至67.46%(见图3A)。给药组荷瘤裸鼠的体质量无显著变化,与对照组相似(见图3B)。

-

本文研究表明:①Fn(1 × 104 CFU/ml)可显著促进直肠癌类器官增殖,且呈浓度依赖(图1),患者衍生的类器官模型表明,Fn的高富集可促进直肠癌的发展,加重病情,严重威胁患者的生命安全,由此可知,在体内抑制Fn的复制、繁殖等可能会为患者带来好处。② 9个抗Fn活性化合物(MIC= 2.0~32 μg/ml)均能显著提升与Fn共孵育结肠癌HCT116细胞的体外抗肿瘤活性,甲氨蝶呤提升抗癌活性幅度最大,达143倍(表1),同时,实时无标记肿瘤细胞生长分析实验显示,甲氨蝶呤也能显著抑制Fn促结肠癌HCT116细胞生长作用,且呈浓度依赖特性(图2)。Fn、细胞、化合物共孵育实验表明,部分化合物在抵抗Fn促增殖作用的同时,可提升其体外抗肿瘤活性,其中,甲氨蝶呤作为经典的抗肿瘤药物,在抗Fn、抗肿瘤细胞以及抗Fn和肿瘤细胞共孵育中均表现出不俗的效果,但产生此效果的机制尚需进一步研究。③优选活性化合物甲氨蝶呤(0.5 mg/kg)与PD-1抗体(5.0 mg/kg)联用,对Fn灌胃干预下裸鼠人结肠癌HCT116移植瘤具有显著的抑制活性,其抑瘤率达67.46%,分别优于相同给药剂量的甲氨蝶呤和PD-1抗体单独用药的抑瘤活性,且对荷瘤裸鼠的体质量无显著影响。从体内实验结果中可知,在Fn高富集的情况下,甲氨蝶呤联合应用PD-1抗体后表现出更好的治疗效果。本研究首先在类器官层面验证了Fn促进直肠癌增殖的效果,其次探索了Fn、细胞同时存在情况下,化合物体外抗肿瘤效果变化,最后根据实验结果优选经典化疗药物甲氨蝶呤,利用裸鼠人结肠癌HCT116移植瘤模型验证了体内效果,并得出基于抗致病具核梭杆菌开发抗结直肠癌的药物具有应用前景的结论。

本研究可为后续抗Fn类抗结直肠癌药物结构衍生提供先导化合物,并有望拓展甲氨蝶呤的新适应证。同时,本文研究仍有部分缺陷,如体内实验没有设置无Fn灌胃干预组,观察无Fn干预情况下裸鼠移植瘤的肿瘤增殖情况,因此,这也为后续深入结构优化所得高抗Fn活性化合物的体内抗结直肠癌活性研究提供改进策略。

Screening and anti-colorectal activity of small molecule inhibitors of Fusobacterium nucleatum

-

摘要:

目的 基于市售化合物库的表型筛选获得抗具核梭杆菌(Fn)活性化合物,评价其在Fn干预下的抗结直肠癌活性,为新型抗结直肠癌药物研发提供先导化合物。 方法 首先验证Fn促结直肠癌类器官增殖效应;其次,比较考察抗Fn化合物在Fn与结肠癌HCT116细胞共孵育下对其体外抗癌活性的影响;最后,评价高活性化合物对Fn灌胃干预下裸鼠结肠癌HCT116移植瘤的体内抗癌药效。 结果 Fn可显著促进直肠癌类器官增殖;9个抗Fn化合物均能显著提升Fn与HTC116细胞共孵育下的体外抗癌活性,其中甲氨蝶呤抗癌活性最强,IC50达0.03 μmol/L;甲氨蝶呤(0.5 mg/kg)与PD-1(5.0 mg/kg)联用能显著抑制Fn灌胃干预下裸鼠人结肠癌HCT116移植瘤的生长,抑瘤率达67.46%,抑瘤效果优于单药。 结论 Fn小分子抑制剂甲氨蝶呤对有Fn干预的结直肠癌细胞和裸鼠移植瘤具有良好的体内外抗癌活性,为后续结构优化打下基础,并有望拓展甲氨蝶呤的新适应证。 Abstract:Objective To screen small molecule inhibitors of Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn) based on commercially available compound libraries, and investigate their anti-colorectal cancer activities under Fn intervention in order to obtain novel anti-colorectal cancer lead compounds. Methods The promotion of colorectal cancer proliferation on organoid was validated by Fn. Secondly, the effects of anti-Fn compounds on their in vitro anticancer activity under Fn’s co-incubation with colorectal cancer HCT116 cell were comparative investigated. Finally, in vivo anticancer efficacy of highly active compounds on nude mouse colon cancer HCT116 transplanted tumor under the intervention of Fn was evaluated by gavage. Results Fn could significantly promote the proliferation of rectal cancer organoids. 9 anti-Fn active compounds could significantly enhance their in vitro anticancer activity under Fn’s co-incubation with HCT116 cells. Methotrexate had the strongest anti-cancer activity with IC50 as 0.03 μmol/L. The combined use of methotrexate (0.5 mg/kg) and PD-1 (5.0 mg/kg) had a stronger anti-tumor effect than their standalone use. Conclusion As new small molecule inhibitor of Fn, methotrexate exhibited good in vitro and in vivo anti-colorectal cancer activity against HCT116 cells and nude mouse xenografts under Fn intervention, which showed the foundation for subsequent structural optimization, and could be expected to expand the new indications of methotrexate. -

Key words:

- Fusobacterium nucleatum /

- phenotypic screening /

- anti-CRC /

- organoids /

- methotrexate

-

表 1 Fn对抗Fn化合物(MIC)的体外抗癌活性(IC50)的影响

名称 MIC

(μg/ml)HCT116

(IC50,μmol/L)HCT116 + Fn

(IC50,μmol/L)新鱼腥草素钠 32 0.48 0.12 对甲氧基苯甲醛 32 4.22 1.77 PA-824 32 9.62 5.62 甲氨蝶呤 32 4.30 0.03 吲哚-3-甲酸 16 8.86 2.72 己烯雌酚 32 23.10 9.35 2'-脱氧胞嘧啶核苷 8 0.78 0.07 5-硝基-8-羟基喹啉 2 22.85 3.93 特地唑胺 2 4.29 1.42 -

[1] SUNG H, FERLAY J, SIEGELR L, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCANestimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [2] RAWLA P, SUNKARA T, BARSOUK A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors[J]. Prz Gastroenterol, 2019, 14(2):89-103. [3] KIMJ Y, HE F, KARIN M. From liver fat to cancer: perils of the western diet[J]. Cancers, 2021, 13(5):1095. doi: 10.3390/cancers13051095 [4] JIA F J, YU Q, WANG R L, et al. Optimized antimicrobial peptide jelleine-I derivative Br-J-I inhibits Fusobacterium nucleatum to suppress colorectal cancer progression[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2023, 24(2):1469. doi: 10.3390/ijms24021469 [5] BENSONA B, VENOOK A P, AL-HAWARY M M, et al. Colon cancer, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2021, 19(3):329-359. [6] KELLAND L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2007, 7(8):573-584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167 [7] WALKOC M, LINDLEY C. Capecitabine: a review[J]. Clin Ther, 2005, 27(1):23-44. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.01.005 [8] CHU D K, ZHANG Z X, LI Y M, et al. Prediction of colorectal cancer relapse and prognosis by tissue mRNA levels of NDRG2[J]. Mol Cancer Ther, 2011, 10(1):47-56. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0614 [9] DAHAN L, SADOK A, FORMENTOJ L, et al. Modulation of cellular redox state underlies antagonism between oxaliplatin and cetuximab in human colorectal cancer cell lines[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2009, 158(2):610-620. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00341.x [10] FAÏS T, DELMAS J, COUGNOUX A, et al. Targeting colorectal cancer-associated bacteria: a new area of research for personalized treatments[J]. Gut Microbes, 2016, 7(4):329-333. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1155020 [11] HARUKI K, KOSUMI K, HAMADA T, et al. Association of autophagy status with amount of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer[J]. J Pathol, 2020, 250(4):397-408. doi: 10.1002/path.5381 [12] CHEN Y Y, CHEN Y, ZHANG J X, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes metastasis in colorectal cancer by activating autophagy signaling via the upregulation of CARD3 expression[J]. Theranostics, 2020, 10(1):323-339. doi: 10.7150/thno.38870 [13] MÁRMOL I, SÁNCHEZ-DE-DIEGO C, PRADILLADIESTE A, et al. Colorectal carcinoma: ageneral overview and future perspectives in colorectal cancer[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2017, 18(1):197. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010197 [14] GUO S H, CHEN J, CHEN F F, et al. Exosomes derived from Fusobacterium nucleatum-infected colorectal cancer cells facilitate tumour metastasis by selectively carrying miR-1246/92b-3p/27a-3p and CXCL16[J]. Gut, 2020: gutjnl-gu2020-321187. [15] XUE Y, XIAO H, GUO S H, et al. Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase expression regulates the survival and proliferation of Fusobacterium nucleatum in THP-1-derived macrophages[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2018, 9(3):355. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0389-0 [16] BROOK I. Fusobacterial infections in children[J]. Curr Infect Dis Rep, 2013, 15(3):288-294. doi: 10.1007/s11908-013-0340-6 [17] COCHRANE K, ROBINSONA V, HOLTR A, et al. A survey of Fusobacterium nucleatum genes modulated by host cell infection[J]. Microb Genom, 2020, 6(2):e000300. [18] HASHEMI GORADEL N, HEIDARZADEH S, JAHANGIRI S, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: a mechanistic overview[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2019, 234(3):2337-2344. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27250 [19] KOSTICA D, CHUN E, ROBERTSON L, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2013, 14(2):207-215. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007 [20] HUI B Q, ZHOU C C, XU Y T, et al. Exosomes secreted by Fusobacterium nucleatum-infected colon cancer cells transmit resistance to oxaliplatin and 5-FU by delivering hsa_circ_0004085[J]. J Nanobiotechnology, 2024, 22(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12951-024-02331-9 -

下载:

下载: